#4) STRENGTH TRAINING

“If you think lifting weights is dangerous, try being weak. Being weak is dangerous.” - Bret Contreras

Resistance Training

Strength training, also referred to as resistance training, is a form of exercise that entails utilizing resistance in order to move your muscles against a force. This can involve using free weights like dumbbells and barbells, weight machines, bands, or even your own body weight.

Training Benefits include:

Training Recommendations:

Early Progressions (start or restart)

Watch this video on putting together your strength program:

Health Benefits

Resistance training offers benefits beyond building muscle. It improves strength and endurance, making daily activities easier, and helps increase bone density, reducing the risk of osteoporosis. It also boosts metabolism by increasing muscle mass, which supports weight management and healthier body composition. Additionally, it enhances mental well-being by releasing endorphins and lowering stress and anxiety.

Performance Benefits

Strength training offers numerous performance benefits, including increased muscle strength and endurance. It also enhances power and explosiveness, improves joint function and stability, enhances balance and coordination, triggers beneficial hormonal responses, aids in injury prevention, and increased confidence. These advantages make strength training a versatile and effective approach to improving physical fitness and overall performance.

Endurance Performance

Strength training can significantly benefit endurance athletes by increasing muscle strength and neuromuscular coordination, leading to more efficient movement and reduced energy cost during prolonged activity (Paavolainen et al., 1999). It improves running economy, cycling efficiency, and delay of fatigue through enhanced motor unit recruitment and increased muscle-tendon stiffness (Saunders et al., 2006). Additionally, strength training helps prevent injuries by strengthening connective tissues and correcting muscular imbalances (Lauersen et al., 2014). These adaptations translate to better performance in activities like running, cycling, and swimming.

Check out this video by Ironman legend Dave Scott

Improving Body Composition

Strength training improves body composition by increasing lean muscle mass and reducing fat mass. It elevates resting metabolic rate due to greater muscle mass, leading to increased daily energy expenditure (Westcott, 2012). Resistance training also promotes fat loss by enhancing insulin sensitivity and stimulating the release of hormones that favor fat oxidation (Strasser et al., 2012). Unlike aerobic exercise alone, strength training helps preserve or even increase muscle mass during weight loss, leading to more favorable body composition changes (Hunter et al., 2008).

Check out this Video by Bret Scher, MD

FUNCTIONAL STRENGTH

And the many Benefits Around Aging

Strength training, once thought to be only for athletes or bodybuilders, is now recognized as a key part of healthy aging and functional living. Emerging research suggests it may even surpass cardio in promoting longevity. Studies show regular strength training is associated with a reduced risk of death from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

The American Council on Exercise (ACE) highlights benefits like increased muscle and bone strength, improved metabolism, and better daily function—key factors for aging well and staying independent.

While more research is needed to confirm causation, current evidence supports strength training as a safe and effective way to enhance long-term health and quality of life.

Here is a video example of an easy to follow Level 1 Strength Workout for Seniors.

Here is a discussion by Peter Attia on ow the brutal facts highlight the Importance of Preventing Accidental Falls through Strength Training

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS

Strength training guidelines

Here are the American College of Sports Medicine strength Training Recommendations:

Essentially, the twofold objective of any strength training program is to enhance fitness, health, and work task performance while reducing the risk for injury. The recommendations outlined below are targeted at fitness-oriented individuals and adhere to the aforementioned objectives.

The strength training program should be performed a minimum of two non-consecutive days each week,

With one set of 8 to 12 repetitions for healthy adults or 10 to 15 (lighter) repetitions for older and frail individuals.

8 to 10 exercises should be performed that target the major muscle groups.

See the complete ACSM handout here.

In summary these guidelines are your minimum requirements.

In the next sections we will discuss specific phases that you may experiment with depending on your goals and the period of time in your plan(s).

Early Progressions

Getting started or re-started

After achieving a foundational level of core stability and establishing a functional range of motion without pain, it becomes essential to progressively enhance resistance loads. This progression is necessary to sustain ongoing improvements in muscle strength, tone, and endurance. It's crucial to challenge all body movements to maintain appropriate muscle balance and functional mobility.

When initiating a new program, it's advisable to begin at an easier level. This phase is known as the anatomical adaptation period (AA strength).

When embarking on a weight-training program, consider following the sample progression provided below:

How do I know how hard to push?

Once you have set a foundation and slowly built up your strength using less than maximal loads over a period of time, it may be time to push to your maximum weight for the reps.

So technically your final repetition would lead to failure! HOWEVER, for most of us in the over 50 crowd we probably should stop earlier, before your form begins to break, usually 1-2 reps before failure.

See this important study review on the benefits of keeping Reps in Reserve Here

Phasic Approach & Common Practices

The foundation of any strength training program should be a strong and stable musculoskeletal system. This starts with exercises that promote muscle balance, proper movement patterns, and correct form—before introducing heavy loads. This initial phase is often referred to as the Anatomical Adaptation (AA) and Core Conditioning phase. During this stage, the focus is on stabilizing the spine, torso, and other vulnerable areas.

Stabilization and functional movement exercises should target all joints relevant to your sport or activity to ensure safe and effective progression. If a fitness assessment identifies issues like poor lumbopelvic control, limited flexibility, or a history of overuse injuries, begin with a daily routine of corrective and core stability exercises.

Defining Training Load: Step Loading

Tudor Bompa, Ph.D., and Carlo Buzzichelli define step loading in Periodization of Strength Training for Sports (4th ed.) as:

“Step loading is the preferred method for inducing morpho-functional adaptations through a gradual escalation of muscular, metabolic, and neural stress over time. Across a macrocycle, it's possible to advance one or more loading parameters in accordance with the desired training effects (adaptations).”

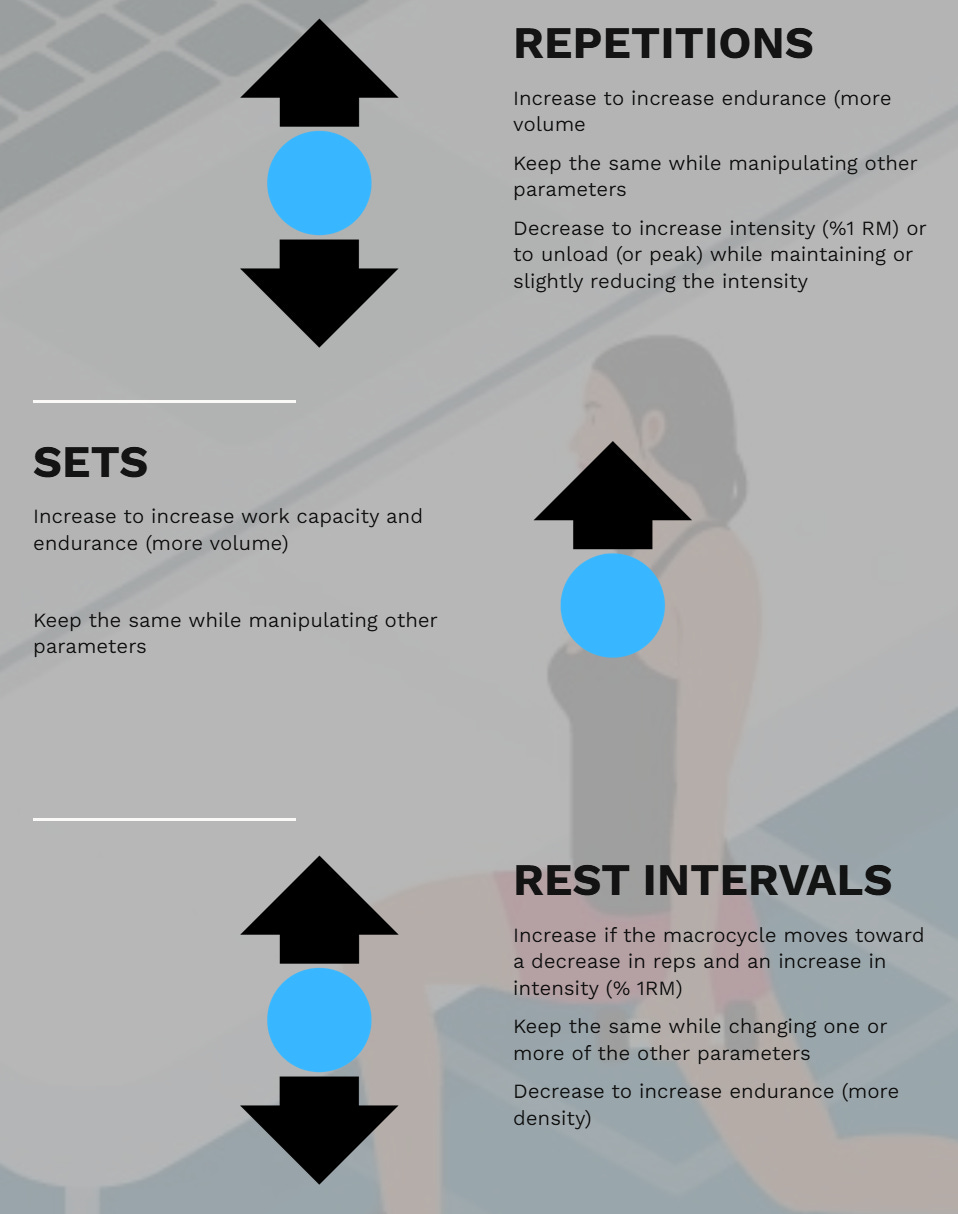

This means you can tailor training loads to target specific adaptations by adjusting key variables like repetitions, sets, and rest intervals:

Choosing Your Training Phase

Here is a table listing the various strength training phases that describe the workout plan.

Choosing Your Workout Skill Level

The phase (e.g, AA, MS, etc.) of your strength training is different than the "level" of your workout. Choosing a training level has more to do with your ability to do the exercise safely and correctly. All levels incorporate four key movement domains;

the push,

pull,

squat (or lunge)

and hip hinge.

Most are multi-joint exercises that are key movement patterns for optimal function and to promote high level physical performance.

There is also an Accessory domain option which can include exercises for individual muscle groups or prehab type exercise.

Essentially we have three levels to choose from when determining the type of exercises you should consider using within your training phase(s). If you are new to lifting or are coming back from a significant layoff due to injury or a sedentary lifestyle then we would recommend you choose the level one exercises until you have been strength training regularly at level 1 for six weeks or more without limitations, and you have been instructed how to do the more complicated lifts found in level 2.

For the level 3 exercises it is recommended that you have spent at least a couple months training with exercises similar to level 2 before including these more advanced exercises into your routine.

See sample exercises here:

Exercise options for true beginners or those coming back from a long layoff

Adding greater form challenges to some exercise options

Includes more complex and advanced exercises for the more experienced exerciser

NOTE: Some individuals may have a very solid lifting background and could begin the level 3 workouts at the get-go even though they are starting in the AA (anatomical adaptation) phase of their training. Whereas some other individuals may have been training for several months and are at the max strength (MS) or power strength (PS) phase while still performing exercises in level 1 or 2 due to their skill, stability or equipment limitations.

Recommended Tracking App

Key References:

Paavolainen, L., Häkkinen, K., Hämäläinen, I., Nummela, A., & Rusko, H. (1999). Explosive-strength training improves 5-km running time by improving running economy and muscle power. Journal of Applied Physiology, 86(5), 1527–1533.

Saunders, P. U., Pyne, D. B., Telford, R. D., & Hawley, J. A. (2006). Factors affecting running economy in trained distance runners. Sports Medicine, 36(7), 559–572.

Lauersen, J. B., Bertelsen, D. M., & Andersen, L. B. (2014). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(11), 871–877.

Westcott, W. L. (2012). Resistance training is medicine: effects of strength training on health. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 11(4), 209–216.

Strasser, B., Arvandi, M., & Siebert, U. (2012). Resistance training, visceral obesity and inflammatory response: a review of the evidence. Obesity Reviews, 13(7), 578–591.

Hunter, G. R., McCarthy, J. P., & Bamman, M. M. (2004). Effects of resistance training on older adults. Sports Medicine, 34(5), 329–348.

JAMA Network Open. "Association of Physical Activity Intensity With Mortality: A National Cohort Study of 403,681 US Adults."

British Journal of Sports Medicine. "Muscle-strengthening activities and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies."

American Council on Exercise (ACE). "The Importance of Strength Training for Older Adults."

Go to next page: Economy of Motion